《意味와 無意味 SENS ET NON-SENS: Works from 1974 to 2020》

| [GALLERIES] Arario Gallery Seoul

2020.11.26 – 2021.2.27

최병소

최병소의 작업세계를 통해 반예술적 태도, 의미의 해체, 그리고 일상적 상황의 활용과 같은 1960-70년대 한국 실험 미술의 실천과 정신을 조명

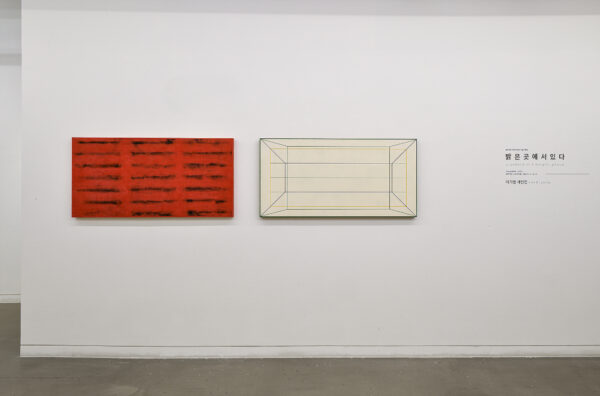

아라리오갤러리 서울은 최병소의 개인전 《意味와 無意味 SENS ET NON-SENS: Works from 1974 to 2020》을 개최한다. 이번 전시는 작가의 예술세계의 근간을 이루는 1970년대 초기 작품과 최근의 작품을 병치시킴으로써 1970년대 초반 전위적 한국 실험미술의 태동과 단색화의 경향을 관통하고 있는 최병소만의 독특한 미술사적 위치를 재고하고자 한다. 전시의 제목 《意味와 無意味 SENS ETNON-SENS》는 작가의 작품 <무제>(1998)에 사용된 메를로 퐁티의 저서(1948)에서 가져왔다. 최병소는 예술과 사회 전반에 존재하는 주류 체계를 부정하며 그 체계를 해체하는 것을 통해 새로운 가능성을 열어두고자 했다. 이와 같은 그의 작업 세계는 이성과 논리 세계의 무의미함을 주장하고 경험과 물리적 경험성의 중시를 주장했던 메를로 퐁티의 세계관과 그 맥이 닿아 있기도 하다.

최병소가 대학에서 미술을 공부하고 활동을 시작했던 1970년대는 5.16 군사 정변과 유신체제에 대한 정치적 좌절감, 그리고 새마을운동으로 인한 경제적 안정과 희망을 동시에 경험했던 시대였다. 젊은 작가들은 일부 개방된 문호를 통해 국제미술의 사회적이고 실험적 미술경향에 대해 접할 수 있었으나 군부독재 하의 상황 속에서 실험적 작업과 전시들은 제재와 억압을 받았다. 국전과 같은 공인된 무대에 설 수 있었던 미술은 추상미술로, 그리고 단색화 사조로 점차 편중되었다. 1970년대 이후 전개되는 모노톤 회화의 집단적이고 조직적인 성격에 비해 현실에 대한 발언을 직간접적으로 시도했던 실험적 미술 활동들은 당시 정권에 대한 항거로 읽혀지며 탄압을 받았고, 이와 같은 경직된 분위기에서 한국의 실험 미술은 그 활동과 위상이 자연스럽게 축소될 수 밖에 없었다. 최병소는 추상미술의 형식성을 일부 계승하기도 하지만 사회적 불평등과 부조리를 직시해야 한다는 예술가들의 실험적인 정신을 실천하며 단색화와 실험 미술 사이의 경계 사이 독자적인 작품 세계를 만들어냈다. 1960년대 후반부터 진행되어온 한국 작가들의 실험적 시도의 원동력에는 형식주의 예술에 대한 저항, 내면으로 침잠하던 추상미술에 대한 반발이 있었다. “순수조형에의 의지의 확인과 실험의 장이자, 20세기 전반부 예술의 지지체였던 팽팽하게 고양된 캔버스의 평면성과 그 조건 위에서 추구되었던 일루져니즘의 미학을 부정한다”라는 언급에서 살펴볼 수 있듯이 최병소의 작업의 기저에는 반예술적 태도가 깔려있다. 그는 신문지, 연필, 볼펜은 물론이고 의자, 잡지 사진, 안개꽃 등 우리가 하찮게 여기는 물건들에게 새로운 의미를 부여함으로써 매체의 순수성, 형식주의 모더니즘과 같은 미술의 위계를 전복시킨다.

과거 작가의 대구 작업실이 침수되어 1970-80년대에 제작된 작품 대부분이 유실 또는 파손되었는데, 이번 전시에서는 현재 남아있는 1970년대 사진 작품으로는 유일한 두 작품을 소개한다. 내셔널지오그래픽 잡지 사진을 이용해 만들어진 <무제 9750000-1>(1975)과 의자 위에 사물을 놓고 촬영한 사진과 문자를 결합한 <무제 9750000-2>(1975)는 사진의 시각 이미지를 언어로 해석 또는 지시해 놓는 작품이다. 작품 속에서 사진의 이미지는 이를 형용하는 문자와 결합되어 새로운 해석의 가능성을 열게 되며, 의미의 차이로 인해 발생하는 우연적이고 필연적인 어긋남을 의도했다는 것을 알 수 있다. 노닐고 있는 두 마리의 새와 그 상황을 설명하는 언어의 결합, 의자에 올려진 사물들과 그 사물을 지시하는 단어들의 결합에서 관람객은 도리어 상황과 현실을 담을 그릇으로 언어가 가진 한계를 경험하게 된다. 1970년대 당시의 작가는 이렇게 시각언어와 문자 언어 간 해석의 차이를 노출시키는 작업을 통해 시각 예술이 언어이자 개념의 영역임을 인지했다는 것을 알 수 있다. 이 네 점의 사진 작품은 비디오, 필름, 퍼포먼스, 이벤트 등의 실험적인 작품들을 선보인 1975년 《대구현대미술제》에 처음으로 출품되었는데, 작가는 당시 이 사진 세트와 함께 접의자 여러개를 배치한 설치 작품 <무제 9750000-3>(1975)도 함께 전시하였다. 여러 개의 의자들은 나란히, 또는 개별로 배치되었으며 의자가 놓인 바닥은 흰색 테이프로 표시되었다. 또한, 의자가 없는 자리의 바닥에 테이프만 둘러져 있기도 한 곳도 있었다. 작가에 의하면 이 의자 설치는 학교의 교실, 학급의 모습에서 착안했다고 하는데, 여기에서는 질서에 순응한 집단과 그로부터 이탈한 개인에 대한 작가의 고찰을 읽어볼 수 있다. 그는 빈 의자들을 사용해 화자와 청자의 관계, 존재와 부재의 차이를 연출함으로써 사회의 규율 속 사라진 사람들의 모습과 흔적만 남은 개인의 역할에 대해 되묻고 있다.

최병소의 대표작으로 잘 알려져 있는 신문 지우기 연작 또한 그가 평생을 매진해온 실험적 정신의 실천이다. 재료비가 거의 들지 않은 일상의 사물을 지지체와 화구로 선택해 탄압의 대상이었던 신문을 까맣게 지우며 사회에 대한 저항의 몸짓을 기록해 나갔다. 오늘날 최병소의 신문 지우기 작업은 자신을 지우는 움직임으로 읽어볼 수 있다. 일상의 물건을 작업에 사용해 한국 사회를 살아가던 최병소 개인과 예술가의 열망을 표현하는 방식은 현장 설치 작품 <무제 016000>(2016)에서도 이어진다. 전시장 바닥을 가득 채운 이 설치 작품은 옷장에 걸려있는 세탁소 철제 옷걸이 한 개를 즉흥적으로 구부려 보는 것에서 시작되었다. 세로 7미터, 가로 4미터를 덮은 8천여개의 가벼운 옷걸이들은 구부러져 백색의 선으로, 그리고 단색의 공간으로 먹먹하게 펼쳐진다. 이 옷걸이들은 신문 지우기 연작의 연필과 같은 의미를 지닌다. 그는 하찮은 물건과 행위 모두 그 시대의 본질을 구성하고 있음을 직시함으로써 예술을 생산해내는 사회에 대한 근본적인 성찰에 이르고 있다. 예술과 반예술, 의미와 무의미 사이의 열린 가능성을 탐색하는 이번 전시를 통해 한 시대를 증언하는 최병소의 실험적 태도를 만나볼 수 있을 것이다.

아라리오갤러리 서울

서울시 종로구 북촌로5길 84

02 541 5701