YU Xiao | 2025 Kiaf HIGHLIGHTS Semi-Finalists

| [INTERVIEW] 2025 Kiaf HIGHLIGHTS

유 시아오

유 시아오 (1)

1. 작품 주제와 작업 방식 위주로 자기소개 부탁드립니다.

저는 침묵 속에 잠재된 트라우마를 물질적인 저항의 언어로 전환하는 예술가입니다. 작업의 중심에는 여성의 몸이 놓여 있으며, 특히 유교적 가치관의 영향 아래 강제적 조기 폐경을 경험한 이들이 겪는, 사회적으로 외면된 소수자의 경험을 다룹니다. 회화는 단순한 재현의 수단이 아니라, 살아 있는 신체로서 기능하며, 이는 곧 담론적 형식의 회화로 이해될 수 있습니다.

작업 방식은 몇 가지 주요한 방법론을 축으로 합니다. 첫째, 캔버스를 자르고 접고 재구성하는 ‘절단의 역전 기법’이 있으며, 이는 회화의 구조를 근본적으로 뒤흔듭니다. 둘째, 정신분석과 포스트모던 이론을 송나라 미학, 도교의 ‘기(氣)’와 ‘허(虛)’ 개념 등 전통 중국 철학과 접합시키는 문화 간 교차적 접근이 있습니다. 셋째, 정서적 조립체로서, 마스킹 테이프 공이나 붉은 점과 같은 물질적 조작을 통해 트라우마적 경험을 번역해냅니다.

저의 작업은 단절에서 출발합니다. 이 단절은 인지적 지식과 신체 감각적 앎 사이의 인식론적 균열입니다. 본인은 캔버스를 절단하고 접으며, 재구성함으로써 전통적으로 회화가 감추어온 요소들을 드러냅니다. 이때 노출된 스트레처바, 날것의 가장자리, 얼룩진 뒷면은 애도의 신체적 흔적이자 감각적 아카이브로 작용합니다. 천을 가르고, 표면을 구기는 이 물리적 행위들은 신체적 상실이 남긴 심리적 및 생리적 균열과 호응하며, 수치의 감각을 창조의 동력으로 전환시키는 제의적 실천이 됩니다.

저는 고대 중국 미학과 현대 철학을 가로지르며 연결 짓습니다. 예컨대 송대 회화의 ‘허(虛)’는 들뢰즈의 되기 (becoming)’와 리오타르의 ‘형상 (figure)’과 접속합니다. 송대 화가가 문인의 명상 공간을 위해 의도적으로 남겨두었던 여백은, 본인의 작업에서 조용히 절규하는 공백으로 치환됩니다. 서구 추상이 순수성과 질서를 지향한다면, 본인은 그 안에 혼돈을 주입합니다. 마스킹 테이프 덩어리, 의도적으로 위치를 벗어난 점들이 회화의 위계를 해체하고, 질서와 불균형 사이의 긴장을 부각시킵니다. 각 제스처는 초문화적 대화의 일부이자, 고통이 침묵속에 매몰되어 있는 것을 거부하는 행위입니다.

저에게 있어 회화는 ‘초월적 만남’의 장소입니다. 이곳에서 신체의 경험과 캔버스의 물질성이 충돌하고, 애도하며, 마침내 자유를 다시 구성해냅니다.

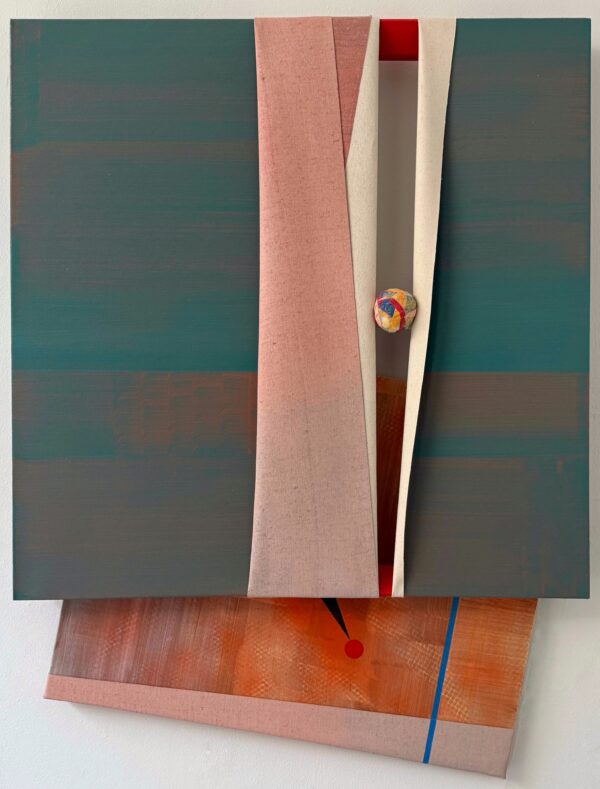

When Slide Up and Down Evokes the Blink No.110. 09, Acrylic and oil paint on canvas and linen, Stained stretcher, previously applied masking tape, Marker pen, 120 x 90 cm, 2024

2. Kiaf SEOUL 2025에서 선보일 작품에 대해 설명 부탁드립니다.

‘Utopia Blink’ 시리즈는 ‘장소가 아닌 곳 (non-place)’이라는 개념을 중심으로 궤도를 그립니다. 이 곳은 구체적인 현실을 넘어선 잠재의 영역이며, 여기서 ‘blink’는 하나의 렌즈이자 점화 장치로 작동합니다. 그것은 원초적이고 호기심 어린 시선으로 주의를 번쩍 깨우는 방식입니다. 이 개념은 테오도르 W. 아도르노에 대한 직접적인 언급 없이도 강렬한 언어적 에너지를 품고 있었고, 저는 그 불꽃을 따라가며 조립적 방법론을 통해 그 충격이 어떻게 새로운 창작 방식의 문을 열어젖히는지를 탐색해왔습니다.

‘다빈치의 거울 (Da Vinci’s Mirror)’은 인식과 시점, 그리고 현실과 추상의 취약한 교차 지점을 조용히 파헤치는 작업입니다. 이 시리즈는 헬레네 시크스의 ‘여성적 글쓰기 (écriture feminine)’와도 긴밀히 얽혀 있으며, 고정되지 않은 표현의 유동성 속에 머문다. 여기서 이 미지들은 고정되기를 거부하며 생각처럼 끊임없이 형태를 달리하고, 그 흐름은 여성의 말로 다 담기지 않는 경험의 층위를 뒤쫓습니다.

두 시리즈 모두에서 저는 회화를 살아 있는 존재로 상상합니다. 그것은 양면에서 호흡하는 감정의 뫼비우스 띠이며, 우아함과 파열이 경계를 두지 않은 채 공존하는 상태입니다. 캔버스는 외과적 정밀함으로 절단되며, 대각선으로 그어진 상흔 아래 드러나는 날것의 린넨은 “더 깊이 들여다보라”고 조용히 속삭입니다. 프레임은 보이는 것 만을 지탱하는 것이 아니라, 보이지 않는 것—빌려오고 간직한, 알려지지 않은 공간의 파편까지—함께 안습니다. 스트레처는 미세한 울림을 담고 있으며, 마스킹 테이프로 만들어진 공은 비밀을 단단히 봉인한 채 감춰둡니다.

송나라 회화의 미학적 원리인 ‘허(虛, emptiness)’는 리오타르가 말한 ‘표현 불가능한 것 (the unpresentable)’과 조우합니다. 그리고 언제나 회화의 겸손한 ‘시종’으로 기능해왔던 스트레처는 이제 계급 조직에게 보란듯이 빛 속으로 걸어 나와 주연의 자리를 차지합니다.

Da Vinci’s Mirror No.60.10/01, Acrylic on Canvas, stained stretcher, previously applied masking tape, 60 x 80 cm, 2025

3. 다른 작가와 구분되는, 본인 작품세계의 가장 큰 특징은 무엇인가요?저의 작업은 세 가지 핵심적 특성을 중심으로 전개됩니다.

첫째는 감각과 감정의 물질화입니다. 애도의 심리적 매커니즘을 시각적 상징으로 전환하여 창조적 에너지로 전유하는 방식입니다. 예를 들어, 공은 난소의 은유로, 절단은 상처의 형상으로 등장하며, 이들은 모두 자율 회화의 하나의 모델로 전환됩니다. 동서양의 이분법을 넘어서기 위해, 본인은 송나라의 미학을 캔버스의 ‘육체’안에 내장시키며, 리오타르가 말한 ‘표현 속의 표현 불가능한 것 (the unpresentable in presentation itself)’이라는 개념과의 잠재적 대화를 유도합니다.

둘째는 수치심이라는 감정에 접근하는 새로운 페미니스트 회화 전략입니다. 이는 경험과 표현을 1:1로 대응시키는 서술 방식이 아니라, 형상 회화를 통해 감정과 신체를 재배열하는 실천입니다. 프리다 칼로가 자신의 삶과 고통을 상징화한 자화상을 통해 보여주었던 전기적 회화 문법과 달리, 본인은 트라우마를 물질적 조우로 추상화합니다. 이 과정에서 스트레처, 공, 공백은 신체의 일부로 작동하며, 경험의 물성을 감각화합니다.

셋째는 회화 내부의 위계 구조를 절단하고 접음으로써 전복하는 방식입니다. 캔버스 뒷면과 스트레처 자체가 새로운 서사의 가능성을 품도록 활성화됩니다. 본인의 절단과 접기는 자가 파괴 예술 (Auto-Destructive Art)처럼 니힐리즘적 제스처가 아니라, 오히려 도교적 변형의 논리에 가까운 회복적 행위입니다. “파열에서 전체저로”라는 도가적 원리와 함께, 이 행위들은 파괴를 통해 생성되는 새로운 형식성과 감각을 탐색합니다.

본질적으로 본인은 회화를 안과 밖으로 전복시킵니다. 스트레처는 더 이상 회화를 지지하는 골격이 아니라, 외피이자 감각의 피부가 됩니다. 공백은 단순한 비어 있음이 아니라, 감정의 합창처럼 울려 퍼지는 공간이 됩니다. 공은 폐기된 잔해가 아니라, 새로운 생명의 은유—난소—로 작동합니다. 바로 이 지점에서, 애도는 침묵이 아니라 혁명의 언어로 변환됩니다.

Gaming of Trio-Monads #23.11, Acrylic on Canvas, 25 x 25 cm, 2023 (1)

4. 전업 예술가로 사는 건 결코 쉽지 않은 일입니다. 작업할 때 가장 큰 어려움은 무엇이었나요? 그럼에도 불구하고 예술을 지속했던 원동력은 무엇이었나요?

가장 큰 도전은 언제나 미래에 존재합니다. 저는 어떤 도전이 일단 극복되고 나면, 그 과정을 둘러싼 장애물들을 빠르게 잊는 편입니다. 그렇게 다시 앞으로 나아가고, 늘 미래를 향해 움직이며, 도전이 결코 사라지지 않는다는 사실을 인식한 채 끊임없이 준비하려 합니다. 이러한 반복은 본인만의 독자적인 경험을 축적하게 만들고, 예술적 감수성과 민감도를 고양시키는 새로운 인식을 열어줍니다. 이는 언제나 흥미롭고, 창작자로서 가장 살아 있음을 느끼게 하는 과정입니다.

저의 원동력이 무엇인지 물어보신다면 동기는 다양하지만, 그 중 특히 인상 깊은 것은 지난해부터 전개된 ‘닷 컨스피러시 (Dot Conspiracy)’라는 작업입니다. 갤러리 가격표 위에 붙은 작고 붉은 점들을 본인은 일종의 ‘반항적인 비밀 요원’으로 상상합니다. 이 유쾌한 발상은 위·진·남북조 시대 장성요가 남긴 지혜—즉, “용을 그리고 마지막에 눈동자를 점으로 찍는 행위로 비로소 용이 살아난다”는 고사—를 떠올리게 합니다. 여기서도 붉은 점은 회화에 생명을 부여합니다. 점이 공과 마주할 때마다, 마치 속삭이듯 질문을 던지는 듯합니다. “이 마스킹 테이프 공 하나가 얼마라고요?!”

창작은 언제나 예기치 못한 불꽃을 일으키며, 그것은 연료처럼 작동해 에너지를 끌어올립니다. 그렇게 해서 혁명이 일어나고, 호기심이 되살아납니다. 더불어 본인의 스튜디오는 일종의 마법같은 기운을 품고 있습니다. 이 공간에 한 번이라도 발을 들여본 사람이라면 누구나 알 것입니다. 스튜디오는 작업에 집중하게 만드는 풍부한 감정 에너지를 품고 있으며, 한 번 들어서면 쉽게 빠져나올 수 없을 만큼 강한 끌림으로 존재를 감쌉니다.

Gaming of Trio-Monads #23.11, Acrylic on Canvas, 25 x 25 cm, 2023 (2)

5. 예술가로서 앞으로 이루고 싶은 목표가 있으신지, 있다면 무엇인지, 요즘 관심이 가는 작품 주제나 소재는 무엇인지 말씀해 주세요.

제 작업에서 목표란 언제나 실천의 흐름 속에서 생겨나는 질문들에 의해 안내됩니다. 예컨대, 특정 예술적 또는 문학적 발견이 회화라는 형식 안에서 어떻게 전시적 조립으로 통합될 수 있는지, 본인의 회화 모델이 본질주의에 빠지지 않으면서도 어떻게 내러티브를 변화시키며 진화할 수 있는지를 지속적으로 탐색해왔습니다. 보다 구체적으로는, 회화가 벽으로부터 완전히 해방되어 ‘초문화적 자궁 (Transcultural Womb)’이라는 몰입형 설치 작업으로 확장되기를 꿈꾸고 있으며, 이러한 작품을 실현할 수 있는 커미션을 받을 수 있기를 바라고 있습니다. 또 다른 제안으로는 갤러리를 침묵이 의례화된 공간으로 변화시키는 것입니다. 이 작업은 ‘수치는 조용한 자연 (Shame is Quiet Nature)’이라는 제목 아래 진행 중이며, 각 제안에 대한 구체적인 기획안은 준비되어 있습니다. 우아한 폭력과 부드러운 저항을 통해 침묵을 전달하는 행위는, 형상 회화를 통해 수치심을 전복하려는 본인의 지속적 작업이자, 새로운 페미니스트 접근법을 더욱 풍부하게 만듭니다.

Gaming of Trio-Monads #23.11, Acrylic on Canvas, 25 x 25 cm, 2023 (3)

6. 이번 Kiaf 하이라이트 전시를 통해 관객들에게 어떤 감동이나 생각, 인상을 남기고 싶으신가요?

저의 작품은 다음과 같은 단어로 표현될 수 있는 감정을 불러일으킬 수 있습니다: 장난스러움, 특이함, 엿보기, 경계 넘기, 우아한 폭력, 반항, 전복, 그리고 재탈환 된 수치의 몸.

저의 작품은 관객에게 촉각적인 괴로움을 줄 수 있습니다. 관객이 난도질 된 작품 앞에 마주 설 때 작품의 상처를 피부로 느끼는 경험을 하시기를 기대합니다. 이러한 생리적 충격은 사회 규범 아래 길들여지거나 은폐 되거나 해체된 몸들이 지닌, 말 없는 언어의 형태로 작용합니다. 조기 폐경이 남긴 수치심은 바로 이러한 방식으로 공유된 신체로 전환됩니다.

이와 함께 전개되는 ‘닷 컨스피러시 (Dot Conspiracy)’는 반란의 방식으로 호기심을 유도합니다. 붉은 점은 윙크 하듯 은밀히 신호를 보내고, 구겨진 마스킹 테이프 공은 “도대체 이게 뭐야”라고 묻도록 도발합니다. 이 작은 반역자들은 전통적인 미술 감상의 구조를 어지럽히고, 경이로움을 자극하는 도발자로 기능합니다. 점은 일종의 구두점처럼 작동합니다. “여기서 멈춰라. 말해지지 않은 것은 무엇인가?” 그리고 끈적이고 반짝이는 스튜디오 노동의 잔여물이자 잔해로 존재하는 공은 불완전함 속에서 아름다움을 찾아내도록 도전장을 던집니다.

이 두 존재는 낙인을 자석처럼 매혹적인 낮섬으로 바꾸어 놓습니다. 그것은 하나의 눈부신 사건이자, 기묘하게 즐거운 놀라움으로 다가옵니다. 더 가까이 다가가서 보시면 캔버스 사이의 간격은 비어 있지 않으며, 그 틈은 그 자체로 생명력을 가집니다.

노출된 스트레처와 날 것의 리넨으로 드러나는 공백 속에서, 본인은 관람자들이 각자의 삶 속에 남겨진 무언가를 발견하길 바랍니다. 가족을 위해 잠시 접어두었던 경력의 조각, 깔끔히 접어 감춰둔 슬픔, ‘비현실적’이라는 말로 봉인된 오래된 꿈. 이러한 개념은 송나라의 ‘허(虛)’ 개념을 오늘의 언어로 새롭게 해석한 것입니다. 그 공허함은 “나 괜찮아”라는 말로 눌러 담긴 수많은 침묵들과 깊게 공진합니다.

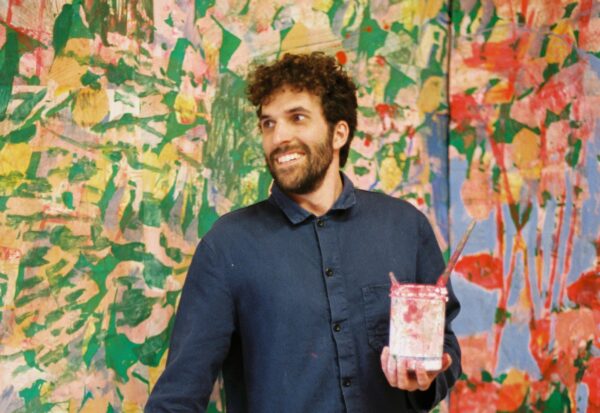

유 시아오 (2)

7. 남기고 싶으신 말이 있다면 자유롭게 해 주세요.

당신의 침묵은 질감을 가지고 있습니다.

당신의 고통은 빛을 품을 수 있습니다.

당신의 빈 공간은 아직 그려지지 않은 풍경입니다.

재구성이 이루어집니다.

세미 파이널리스트 10인으로 선정된 이들의 작품은 Kiaf SEOUL 현장의 각 갤러리 부스에서 만나 보실 수 있습니다.

[INTERVIEW] 2025 Kiaf HIGHLIGHTS

- Artists

- 유 시아오