Grim Park | 2025 Kiaf HIGHLIGHTS Semi-Finalists

| [INTERVIEW] 2025 Kiaf HIGHLIGHTS

박그림

박그림 작가

1. 작품 주제와 작업 방식 위주로 자기소개 부탁드립니다.

저는 한국화에서 불교미술의 형식과 기법을 기반으로, 퀴어 정체성과 자전적 서사를 결합하여 동시대의 종교화를 그리는 박그림입니다. 제 작업은 “불화의 형식과 퀴어서사의 결합을 통해 이분법적 사회안에서 퀴어정체성이 평등의 시선으로 자리할 수 있을까”라는 질문에서 출발합니다. 전통 불화는 신성한 존재나 절대적인 도상을 반복 재현하는 형식이지만, 저는 그 안에 제 존재를 특히 비정형적 젠더 정체성과 퀴어한 감각, 서사를 어떻게 조심스럽고도 분명하게 끼워 넣을 수 있을지를 고민합니다. 이를 통해 이분법적 고정관념의 경계를 허물고 비주류의 주류화를 시도하며 혐오의 시대가 아닌 평등의 시대를 염원하며 작업해오고 있습니다. 비단 위에 동양과 서양의 재료를 혼용해 작업하며, 등장인물과 서사는 제 시선으로 재구성합니다. 예를 들어 《심호도(尋虎圖)》 연작에서는 ‘깨달음을 찾아가는 여정’을 통해 자아와 욕망, 인간관계에서 오는 깨달음 사이의 경계를 퀴어적인 방식으로 서사화하고 있습니다. 겹겹이 색을 쌓고, 선을 정성스레 긋는 그 과정은 마치 수행처럼, 또는 하나의 존재를 공양하는 행위처럼 다가옵니다.

‘선택받지 못한 자’, ‘경계에 선 존재들’, ‘무명의 이들’을 상징적 인물로 불러내어 그들을 위한 동시대의 종교화를 그립니다. 전통을 빌려 현재를 말하고, 과거와 현재가 충돌하는 접면에서 새로운 신화를 만들어내는 것이 제 작업의 핵심입니다. 정체성은 고정된 것이 아니기에, 매번 다른 방식으로 그리고 또 그려보는 그 반복이 저에게 있어 예술이자 믿음, 탐색, 그리고 존재의 기록입니다.

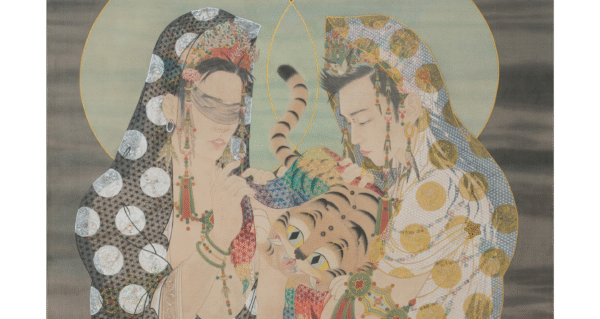

심호도-간택 Shimhodo – Chosen, 2018, Korean traditional painting on silk, 70 × 92 cm

2. Kiaf SEOUL 2025에서 선보일 작품에 대해 설명 부탁드립니다.

Kiaf SEOUL 2025에서는 제 작업 중 하나인 《심호도_간택》을 중심으로, 개인전 《사사 四四》에서 선보였던 회화들을 확장한 형식으로 소개할 예정입니다.

《심호도_간택》은 불교의 ‘심우도(尋牛圖)’ 설화를 차용해, 제 자전적 서사와 결합한 작업입니다. 전통 회화의 형식을 동시대의 맥락 속에 구현하며, 종교화의 구조를 끌어와 퀴어 서사를 수용하는 방식을 연구합니다. ‘심우도’는 한 소년이 소를 통해 자신의 본성을 발견하고 깨달음에 이르는 과정을 그린 이야기인데요, 이 작업에서는 그 ‘소’를 ‘호랑이’로 치환함으로써 깨달음을 주는 존재와 그것을 추구하는 존재의 위치를 재구성했습니다. ‘간택’이라는 제목은 언뜻 보면 절대자가 하위 존재를 고르는 장면처럼 읽히지만, 저는 이 장면을 거꾸로 뒤집어 ‘스스로를 선택하는 퀴어한 주체’의 서사로 읽고자 했습니다. 호랑이는 제 자신이기도 하고, 늘 곁에 있지만 결코 완전히 잡히지 않는 존재이기도 합니다. 호랑이는 한국 문화 속에서 영물로 여겨지지만, 단군신화에서는 결국 인간이 되지 못한 채 배제되는 존재입니다. 저는 이 불완전함의 정체성이 오늘날 혐오와 차별 속에서 존재를 부정당하는 퀴어들의 위치와 맞닿아 있다고 느껴, 호랑이를 제 작업의 페르소나로 삼고 있습니다.

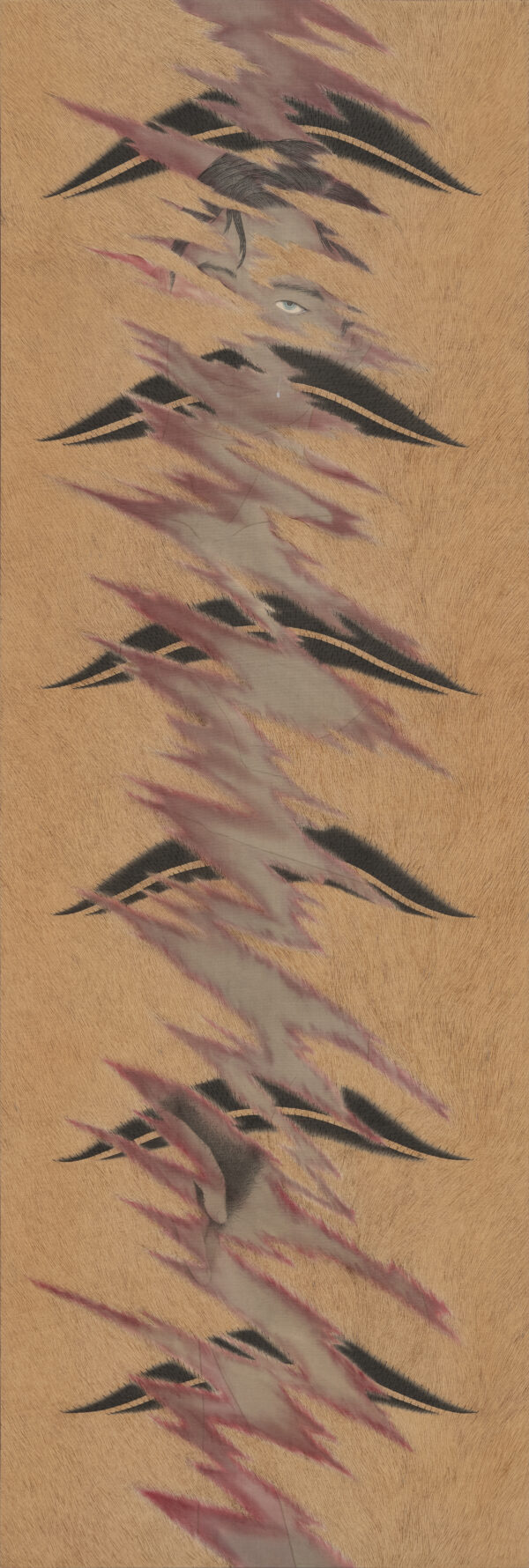

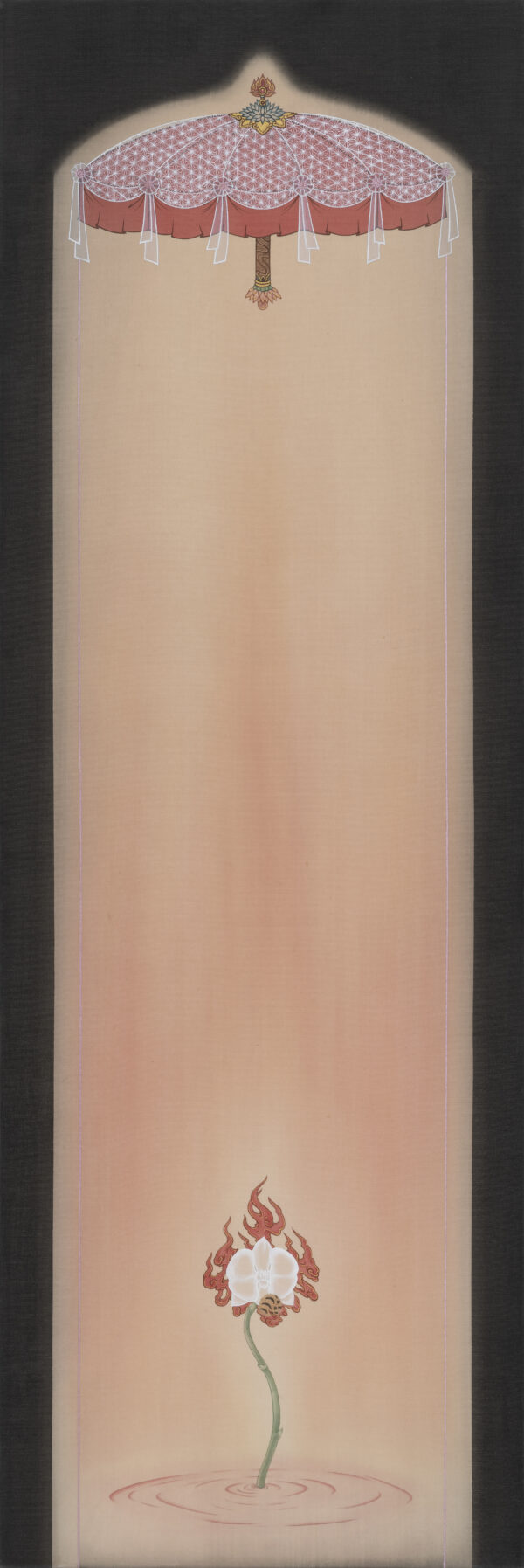

《사사 四四》는 기존 《심호도》 시리즈의 연장선에서, 인물이 제거된 화면 위에 상징적 오브제들만으로 구성된 작품들입니다. 겉으로는 전통 도상의 양식을 따르지만, 그 안에는 숨겨진 이중 구조와 퀴어 코드가 교차하고 있습니다. 이 작업은 단순한 재현을 넘어, 기존의 서사를 재해석하고 변주함으로써 복수의 자아가 순환하는 퀴어 정체성과 감각, 그리고 불교의 윤회사상을 시각화하는 시도입니다.

이번 Kiaf에서는 이 두 작업의 흐름을 따라, ‘깨달음’이라는 개념이 반드시 금욕적이고 초월적인 방식으로만 이루어지는 것이 아니라, 몸을 감각하고, 흔들리고, 욕망하는 과정 속에서도 충분히 일어날 수 있다는 메시지를 전하고자 합니다. 불화의 언어로 퀴어 서사를 말하는 이중적 시도 속에서, 관람자 또한 각자의 ‘간택’과 마주하게 되기를 기대합니다.

我謎 아미 Enigma 2024 Korean Traditional Paint on Silk 120x40cm

3. 다른 작가와 구분되는, 본인 작품세계의 가장 큰 특징은 무엇인가요?

제 작업세계의 가장 큰 특징은 한국 전통 불교미술의 양식과 기법을 기반으로 하되, 퀴어 정체성과 젠더, 사회적 경계에 놓인 존재들을 주제로 삼는다는 점입니다. 한국화와 불교미술, 특히 비단에 담채하는 방식은 오랜 시간과 공력이 필요한 기술이지만, 저는 이 형식을 오늘의 가장 현대적이고 민감한 서사와 연결하려 합니다. 또 하나의 특징은 그림 속 인물들이 대체로 ‘신격화’되어 있다는 점입니다. 저는 이름 없는 존재들, 사회적 규범에서 벗어난 이들, 성소수자와 소외된 이들을 부처나 성인의 형상으로 현현 시킵니다. 그들을 숭배하고 경배하는 존재로 승화시킴으로써, 보편적 인간 존엄성과 이분법적 고정관념의 경계에 대해 이야기하며 비주류의 주류화를 시도합니다.

즉, 전통과 동시대의 충돌, 경계인들의 신화화, 감정과 관계, 욕망의 섬세한 시각화 이 세 가지가 제 작업의 핵심이며, 이는 다른 작가들과 저를 구분 짓는 중요한 지점이라고 생각합니다.

春盖 춘개 Spring Umbrella 2024 Korean Traditional Paint on Silk 120x40cm

4. 전업 예술가로 사는 건 결코 쉽지 않은 일입니다. 작업할 때 가장 큰 어려움은 무엇이었나요? 그럼에도 불구하고 예술을 지속했던 원동력은 무엇이었나요?

작업을 하면서 가장 크게 마주해온 어려움은 존재의 경계에서 살아간다는 감각이었습니다. 제가 다루는 불교미술은 한국 미술사 속에서 굉장히 보수적인 맥락을 가지고 있고, 동시에 제가 몸담고 있는 퀴어 커뮤니티나 정체성은 사회로부터 종종 배제되어 왔죠. 그러다 보니 불화를 그리는 손과, 그 안에 제 정체성을 담으려는 마음 사이에 끊임없는 긴장이 생깁니다. 어떤 날은 제 작업이 ‘이질적이다’, ‘불경하다’는 시선을 직접적으로 마주치기도 했고, 또 어떤 날은 미술 제도 안에서 ‘너무 전통적’이라며 동시대성에 맞지 않는 현대미술이 아니라는 얘기도 들었습니다.

그럼에도 불구하고 계속 작업을 이어올 수 있었던 건, 결국 그림이 저 자신을 가장 솔직하게 마주하게 해주는 방식이기 때문이에요. 언어로는 다 설명할 수 없는 감정들 불안함, 희미한 기쁨, 관계와 정체성에 대한 감각과 생각들을 비단 위에 한 겹 한 겹 쌓아 올리다 보면, 어느 순간 그것들이 사라지거나 덜 중요해지는 경험이 있었어요. 그리고 무엇보다, 제 작업을 보고 “자신의 존재가 조금 덜 이상하게 느껴졌다”고 말해주는 어떤 분들의 목소리가, 예술을 지속할 수 있게 해주는 아주 현실적이고 구체적인 원동력이 됐습니다.

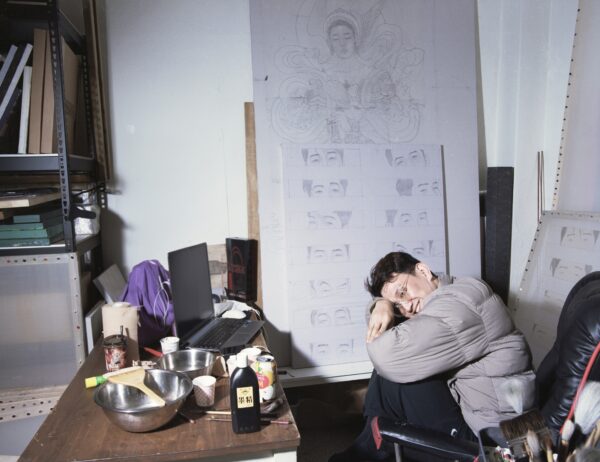

박그림 작가 작업실 전경_사진제공 THEO_촬영 장지원

5. 예술가로서 앞으로 이루고 싶은 목표가 있으신지, 있다면 무엇인지, 요즘 관심이 가는 작품 주제나 소재는 무엇인지 말씀해 주세요.

제가 예술가로서 가장 이루고 싶은 목표는 한국화의 언어로 퀴어한 삶을 세계에 말하는 것, 그리고 비주류 정체성들이 미술계 안팎에서 당연한 존재로 자리잡는 시대를 여는 데 조금이나마 기여하는 것입니다.

전통 한국화, 특히 불교회화는 오랜 시간 동안 특정한 신성함과 권위를 상징해왔고, 그만큼 동시대미술에서 배제되는 것도 강력했습니다. 저는 그 언어를 비틀거나 부정하지 않고, 오히려 그 안에서 퀴어정체성 그리고 관계와 욕망, 흔들리는 자아들을 정중하게 드러냄으로써 이 세계에 더 넓은 정의를 제안하고 싶어요. 그것이 단지 개인적 서사에 머물지 않고, 전통이라는 것을 넘어 보다 확장된 틀로 다시 바라보게 만들 수 있기를 바랍니다.

요즘 특히 관심이 가는 주제는 ‘보이지 않는 존재가 어떻게 신성화되는가’에 대한 질문이에요. 역사 속 불화 도상들을 보면, 늘 정해진 인물이 반복되고 있어요. 그런데 지금 우리가 살아가는 현실은 그보다 훨씬 복잡하고 다층적이죠. 저는 그 ‘복잡함’ 자체를 제 회화의 미덕으로 삼고 싶습니다. 즉, 단순한 정체성의 주장보다 더 넓은 감각 불안, 부유, 결핍, 기쁨이 모두 동시에 화면에 떠오를 수 있도록요.

제가 생각하는 평등은 ‘동일함’이 아니라, ‘다름이 함께 존재할 수 있는 구조’입니다.

그런 시대를 만들어가기 위해, 저는 계속 깨끗한 비단 위에 낯선 존재와 관계들을 그려 넣을 거예요. 그것이 언젠가는 ‘주류’라 불리는 언어 속에 스며들 수 있기를 기대하면서요.

2023 Songeun PANORAMA Exhibition_사진제공 송은_촬영 김재범

6. 이번 Kiaf 하이라이트 전시를 통해 관객들에게 어떤 감동이나 생각, 인상을 남기고 싶으신가요?

이번 Kiaf에서 제가 가장 바라는 건, 제 작업을 마주한 관객들이 ‘이질적이지만 낯설지 않은 감각’을 경험하는 것이에요. 전통 불교회화의 형식을 따르고 있지만, 화면 속 존재들은 익숙한 도상과는 조금 다르고, 그 표현방식이나 표정에는 설명되지 않는 어긋남이 있습니다. 그 틈에서 관객이 ‘이게 뭐지?’라는 질문을 던질 수 있다면, 그 자체가 제 작업이 작동하고 있다는 증거라고 생각해요.

《심호도_간택》에서는 깨달음을 향해 가는 길이 꼭 경건하거나 이상적일 필요는 없다는 것을 말하고 싶었습니다. 진리는 일탈 안에서도, 욕망 안에서도, 자기 자신을 간택하는 순간 안에서 깃들 수 있다는 것. 그 감각을 불화의 언어로 번역해보고 싶었어요. 마찬가지로 《사사 四四》에서는 인물이 사라지고 제 작품의 양식화된 오브제들을 통해 정체성이 고정되지 않은 채 유동할 수 있다는 점을 시각적으로 이야기 하고 싶었습니다.

Kiaf라는 공간은 그 자체로 제도적이고, 상업적인 맥락도 강하지만, 그렇기 때문에 더욱 비가시적인 존재나 서사들이 명확히 드러날 수 있는 장(field)이기도 하다고 생각합니다. 이번 Kiaf를 통해 관객들이 스스로의 내면을 조용히 들여다보거나, ‘나도 혹시 저런 경계 위에 있는 사람일까?’하는 질문을 떠올리게 된다면, 그걸로 충분하다고 느낍니다. 제가 궁극적으로 남기고 싶은 인상은 ‘그림이 말을 걸었다’는 느낌이에요. 큰 감동이 아니어도 괜찮아요. 아주 작고 조용한 균열 하나면 충분하다고 믿습니다.

7. 남기고 싶으신 말이 있다면 자유롭게 해 주세요.

지금 이 시대에 불화를 그리고, 퀴어한 시선으로 전통과 현대를 이어 다시 말하는 일이 얼마나 외롭고, 때로는 불가능처럼 느껴지는 일인지 저 자신이 누구보다 잘 알고 있어요. 그럼에도 불구하고 제가 붓을 들고 화면을 채우는 이유는, 이 길 위에도 누군가가 있었다는 기록을 남기고 싶어서입니다.

제 작품으로 평등의 시대를 희망하는 일은 때로는 너무 크고 멀게 느껴지지만, 사실은 아주 작은 존재가 자신의 자리를 긋는 일이라고 생각해요. 제가 그리는 보살의 얼굴, 깨달음을 갈망하는 호랑이, 무던히, 말없이 자리하며 한 방향을 바라보는 자아들은 모두 그런 마음에서 출발했습니다. 제 작업이 정답을 제시하진 않지만, 누군가에게 ‘이래도 괜찮다’는 감각 하나를 허락할 수 있다면, 그 자체로 충분히 제 작품이 할 수 있는 역할이라고 믿습니다.

세미 파이널리스트 10인으로 선정된 이들의 작품은 Kiaf SEOUL 현장의 각 갤러리 부스에서 만나 보실 수 있습니다.

[INTERVIEW] 2025 Kiaf HIGHLIGHTS

- Artists

- 박그림